Can Harley Quinn and the Birds of Prey call me Doctor Birdie? (October 15, 2021)

Because professors litter lectures with curated pop culture references and stale dad-jokes, my job requires versing myself with DC and MCU and it has nothing to do with Thor’s biceps. So, for work, I binged the latest animated incarnation of Harley Quinn: a brilliant exploration where HQ severs her identity as joker’s girlfriend, yet struggles to be taken seriously because she’s a girl. Love the feminism, but come on: give the emancipated anti-hero her academic accolades! Dr. Harley Quinzel, PhD from Gotham University in Psychology (or MD since she practices psychiatry? Batman should check her credentials).

Prepared to tackle the comic multiverses for fictional academic sexism, I fell into Dr. Strange’s sanctum santorum of reddit threads, top 10 lists, and Wiki fandoms. I was shocked that scholarly women were well-represented on the pulp pages. Comic ladies with accolades -- Karla Sofen, Victoria Montesi, Fazia Hussain, Cecilia Reyes, Linda Carter, Kimiyo Hoshi – also show ample inclusion efforts. Some even had compelling backstories, like Jane Foster who wielded Thor’s hammer without sculpted biceps, and deployed her medical trainings through an epic battle with cancer. Minus the Asgardian subplot, this was comparable to academia where women are reaching parity in many fields with impressive improvements even in notorious STEM fields[i],[ii].

Character arcs for the XX-men also reflect hyperbolized academic struggles, mutating mental health backstories into Daily Bugle headlines about “going insane” when snares engulf careers. Consider Harley Quinn’s roomie, Poison Ivy, who received her PhD in advanced botanical biochemistry until she was poisoned by her professor – ahem – Dr. Jason Woodrue. This "women in refrigerators" phenomenon is reflected in the real ivory tower where parity is chipped away, shedding talent at each career stage, until the upper echelon looks painfully like the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: all dudes. Among STEM doctorates, females are more likely than males to be employed in temporary positions than in top leadership roles1,2 and inequality persists.

Is one barrier that heroines have doctorates, but only heroes are called doctor? Maybe… Of the top 10 comic characters with doctor in their name, all are men. 11 comic villains masquerade without credentials. Doctor Doom tops both lists: an undergraduate drop-out, Doctor Doom was too brilliant to need validation through graduate training. Plot twist! Graduate students struggle to feel validated, especially female and BIPOC scholars [iii]. Imposter syndrome plagues those climbing the ivory tower, not from an unbridled desire for perfection, but rather immersion in a culture that demands excellence but punishes those who succeed in a meritocracy. Displaying too many or too few feminine traits leaves many scholars feeling they don’t belong in an alternative reality called "The Boys" .

Maybe… Of the top 10 comic characters with doctor in their name, all are men. 11 comic villains masquerade without credentials. Doctor Doom tops both lists: an undergraduate drop-out, Doctor Doom was too brilliant to need validation through graduate training. Plot twist! Graduate students struggle to feel validated, especially female and BIPOC scholars [iii]. Imposter syndrome plagues those climbing the ivory tower, not from an unbridled desire for perfection, but rather immersion in a culture that demands excellence but punishes those who succeed in a meritocracy. Displaying too many or too few feminine traits leaves many scholars feeling they don’t belong in an alternative reality called "The Boys" .

It is infuriating when lettered ladies are stripped of their prestige, like Dr Linda Carter, the Night Nurse. Does scholarly respect may also evade men? Dr. Reed Richards, the smartest man on earth, prefers (for obvious reasons) the humble title “Mister Fantastic”. Tony Stark may have one PhD or seven, or only three MIT master’s degrees because “Dr.” Stark intimidates mentees like Peter Parker. Mister Freeze preserves his airtight secret alter-ego’s identity by refraining from being Dr. Freis. Dr. Essex retained his PhD as he morphed into Mister Sinister even though his participant recruitment strategies would horrify even WWII HYDRA eugenicists. Modest entitlement is also reflected in academia. [White] men gain points for being approachable[iv]: “call me Lizard; Dr. Lizard is my father”. Women are assumed to desire being approachable and called by first names, and then recoiled with icy stares that would make Dr. Killer Frost boil when titles are retained. Knowing approachability points would be lost, we remain silent at the slights, put-downs and micro-aggressions.[v]

My most egregious put-down was fodder for an anti-hero backstory when a salesman peddled pink vinyl gloves for my ‘lady fingers’. Facing such condescension, I brandish my Doctorate title with stinging sarcasm that would make Dr. Janet van Dyne proud. Yet men are assumed to be doctors in the strips: And not just doctors! Bruce Banner morphed into the hulk when billed tuition for 7 PhDs. The king of Wakanda has 5 doctorates. Dr. Strange, MD and PhD, keeps his medical license through magic. Professor Charles Xavier earned three doctorates without reading the minds of Oxford teachers. Mister Terrific holds the student loan debt record with 14 doctorates.

My most egregious put-down was fodder for an anti-hero backstory when a salesman peddled pink vinyl gloves for my ‘lady fingers’. Facing such condescension, I brandish my Doctorate title with stinging sarcasm that would make Dr. Janet van Dyne proud. Yet men are assumed to be doctors in the strips: And not just doctors! Bruce Banner morphed into the hulk when billed tuition for 7 PhDs. The king of Wakanda has 5 doctorates. Dr. Strange, MD and PhD, keeps his medical license through magic. Professor Charles Xavier earned three doctorates without reading the minds of Oxford teachers. Mister Terrific holds the student loan debt record with 14 doctorates.

Training timelines flash across the pulp pages from PhD(s) to famous lab director with endless resources and money. In reality, the path to success might land you in Arkham: scientists get their first R01 grant at 43 years on average, and stakes rise from there.[vi] Setbacks disproportionately land on women[vii] who cite more home-life responsibilities[viii],[ix] and utilitarian career sacrifices[x]. More women than men are unemployed after receiving their doctorate, often faced by the maternal wall. When they achieve tenure, most women STEM stars desire to leave academia7. Like in the comics, women more often fulfill side characters or supporting roles. In joining the Fantastic 4 and marrying Mister Fantastic, Dr. Sue Richards became the Invisible Woman.

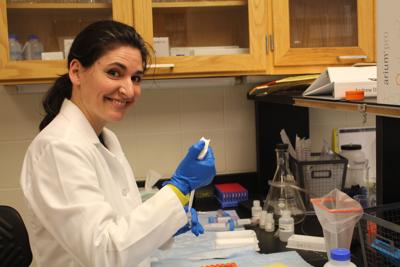

After 20 years and only one PhD[xi], I am a professor with a white lab coat and blue vinyl gloves. My career has not befallen the wrong side of the Blip when, in this very-real universe, it feels like some all-powerful dude snapped his fingers and half my colleagues’ careers turned to dust. This animated masterpiece has given me updated cultural references and inspiration. I want to give Harley Quinn her accolades and a spare hair tie. If she lets me join the Birds of Prey, my secret alter-ego will be Doctor Birdie. And she’s got a great character arc.

[1] Hoffer, Thomas B.; Hess, Mary; Welch, Vincent Jr.; Williams, Kimberly. (2007). Doctorate Recipients from United States Universities: Summary Report 2006. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center. (The report gives the results of data collected in the Survey of Earned Doctorates, conducted for six federal agencies, NSF, NIH, USED, NEH, USDA, and NASA by NORC.) http://www.norc.org.SED.htm

[2] National Science Foundation, Directorate for Social, Behavioral, and Economic Sciences: Doctorate Recipients from U. S. Universities. (2009). National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resource Statistics. (The report gives the results of data collected in the Survey of Earned Doctorates, conducted for six federal agencies, NSF, NIH, USED, NEH, USDA, and NASA.) http://www.NSF.gov/statistics/nsf11306/

[3] Stout, Jane G.; Dasgupta, Nilanjana; Hunsinger, Matthew; McManus, Melissa A. (2011). STEMing the Tide: Using Ingroup Experts to Inoculate Women’s Self-Concept in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol. 100, No. 2, p. 255-270.

[4] Jacobs, Jerry A. and Winslow, Sarah E. (2004). The Academic Life Course, Time Pressures, and Gender Inequality. Community, Work, and Family. Vol. 7, No. 2, p. 143-161. http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

[5] Sumner, Seirian and Pettorelli, Nathalie. (2011). The high cost of being a woman. New Scientist. Vol. 211, Issue 2821, p. 26-27.

[6] Baker, Beth. (2011). Having a Life in Science. Bioscience. Vol. 61, Issue 6, p. 429-433.

[7] Rosser, Sue V. and O’Neil Lane, Eliesh. (2002). Key Barriers for Academic Institutions Seeking to Retain Female Scientists and Engineers: Family-Unfriendly Policies, Low Numbers, Stereotypes, and Harassment. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering. Vol. 8, p. 161-189.

[8] Martinez, Elisabeth D.; Botos, Jeannine; Dohoney, Kathleen M.; Geiman, Theresa M.; Kolla, Sarah S.; Olivera, Ana; Qiu, Yi; Rayasam, Geetha Vani; Stavreva, Diana A.; Cohen-Fix, Orna. (2007). Falling off the academic bandwagon. European Molecular Biology Organization. Vol. 8, No. 11, p. 977-981.

[9] Morgesun, Frederick P.; Seligman, Martin E. P.; Sternberg, Robert J.; Taylor, Shelley E.; Manning, Christina M. (1999). Lessons Learned From a Life in Psychological Science: Implications For Young Scientists. American Psychologist. Vol. 54, No. 2, p. 106-116.

Elizabeth Shirtcliff defied her parents' wishes early and insists on being called Birdie. An unexpected 7.8 earthquake in 1989 and an asbestos fallout when she was 11 left her without any visible superpowers. Seeking again to upend her parents' plans, she excelled in school, beginning college at age 14 and graduated with only one doctorate at 24. Despite her decades of experience in academia, she has yet to receive an R01 grant.

Elizabeth Shirtcliff defied her parents' wishes early and insists on being called Birdie. An unexpected 7.8 earthquake in 1989 and an asbestos fallout when she was 11 left her without any visible superpowers. Seeking again to upend her parents' plans, she excelled in school, beginning college at age 14 and graduated with only one doctorate at 24. Despite her decades of experience in academia, she has yet to receive an R01 grant.